History of Gerrymandering

America was still taking shape when politicians figured out how to game the system.

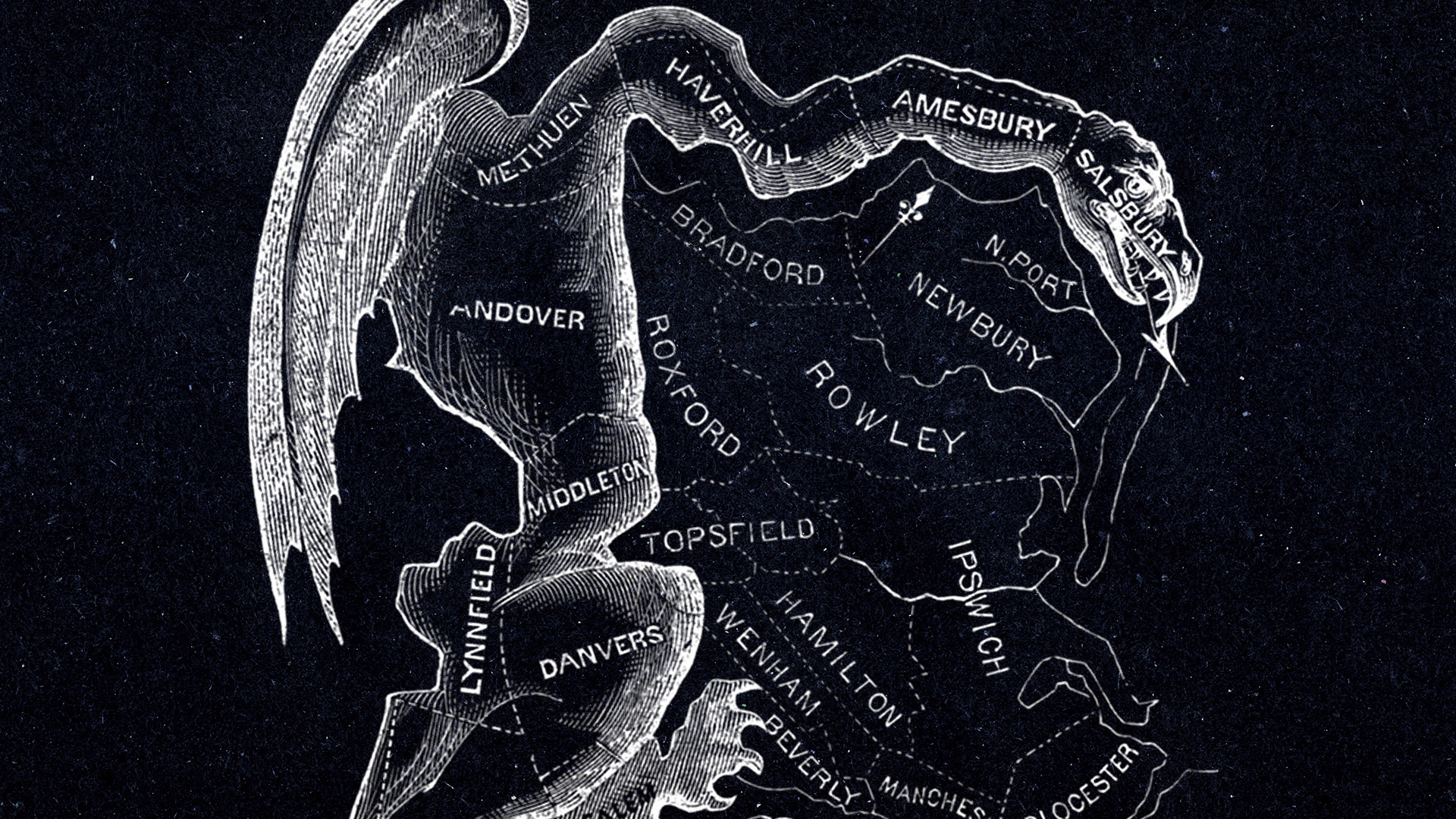

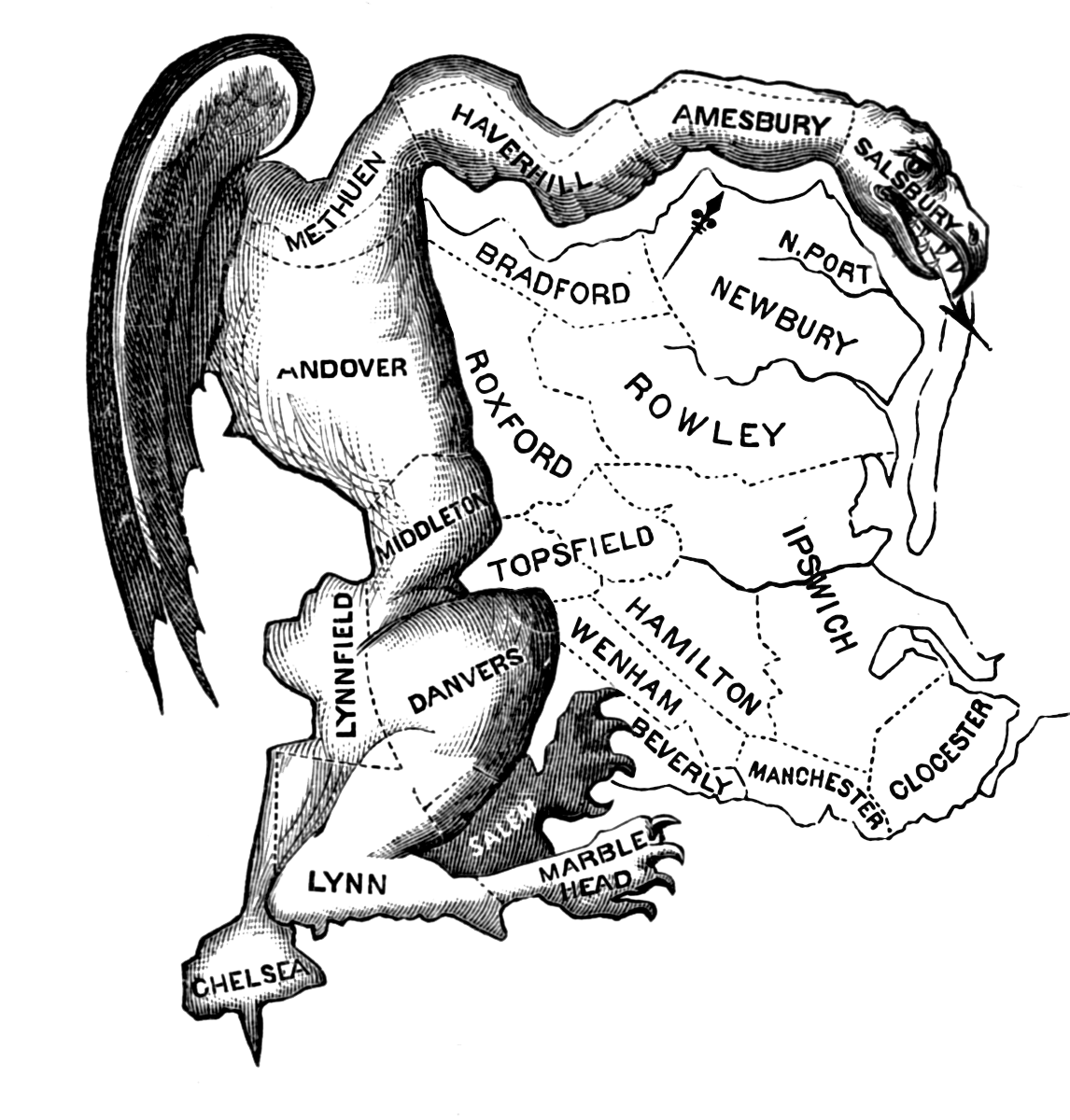

In 1812, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry and his Democratic-Republican allies redrew Massachusetts’ state districts to tilt the balance of state power in their favor. They concentrated Federalist voters into a few districts, while spreading Democratic-Republican voters across many districts to maximize their influence — a tactic that is now known as “cracking and packing.”

And it worked: the results gave Gerry’s party control of the state senate, even though the map was distorted and unfair.

The scheme, however, drew public backlash. That same year, the Boston Gazette published a political cartoon depicting one of the districts in Essex County as a salamander. The Gazette labeled it the “Gerry-mander,” and the name stuck.

Gerrymandering in the 20th Century

Gerrymandering and other discriminatory voting practices spread alongside the country’s politics.

But a major turning point came in the 60s, when The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, and made possible because of the heroic efforts of civil rights activists.

The VRA was a landmark piece of legislation and the crown jewel of the civil rights movement. Simply put: the VRA was meant to prohibit racial discrimination in voting practices and redistricting, and protect the rights of minority voters.

There are two widely cited sections of the VRA when it comes to redistricting: Section 2 and Section 5.

Section 2 prohibits any voting law, practice or map that results in the “denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

Section 5 of the VRA required certain states with a history of racially discriminatory voting practices to get federal approval for any changes to their electoral maps or voting laws, a process known as pre-clearance.

And the law was effective — voter registration and participation increased, discriminatory voting practices and maps were blocked. But it wasn’t a perfect solution — voters of color still faced (and do face) structural barriers to voting.

The preclearance provisions were set to sunset in 1970—but Congress voted to reauthorize them four times. The last time they were renewed was in 2006, when the House voted 390–33 and the Senate 98–0 before being signed into law by President George W. Bush.

Gerrymandering in the Modern Era

Following the 2010 Census, during the 2011 redistricting cycle, Republicans executed a coordinated redistricting gameplan to fundamentally change the landscape of American politics: Project REDMAP.

Republicans strategically invested in state legislative races and other key elections in swing states like Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Florida, and Michigan so they could control the map-drawing process after the 2010 census. This was the core of Project REDMAP. By winning these statehouses, Republicans positioned themselves to dominate redistricting behind closed doors. Once in power, they surgically manipulated both state legislative and congressional maps across the country—cracking apart communities, packing Democratic voters into as few districts as possible, and engineering huge partisan advantages that lasted for an entire decade.

As a result, throughout the decade, Republicans used this artificial power to advance right-wing priorities that are out of touch with the majority of Americans, including limiting access to abortion, blocking common-sense gun control measures, failing to curb the impact of climate change, and making it harder for people to vote.

So we knew we needed to level the playing field. In 2017, ahead of the 2020 Census and 2021 redistricting cycle, the NDRC was founded to shift the balance of power away from total Republican control of redistricting, raise awareness of redistricting and empower the public to get involved in the fight for fair maps.

Another major turning point in this fight against gerrymandering was in 2019, when the Supreme Court dealt a major blow to the fight for fair maps in Rucho v. Common Cause. The Court ruled that federal courts could not decide cases of partisan gerrymandering, leaving it up to states to police themselves — and leaving millions of voters trapped in unfair districts.

So we had to work even harder to ensure America could be a truly representative democracy. And in 2022, thanks to our efforts, and the efforts of thousands of Americans who mobilized for fairness, The New York Times declared the congressional map “the fairest this nation has seen in 40 years.”

But in June 2025, that all changed when President Trump unleashed a plan to gerrymander as many states as possible, starting with Texas, which kicked off a nationwide redistricting race.

Our fight is now. Are you in?

Every generation of Americans is called upon to defend democracy and to bring our nation closer to its founding ideals. It's now our time to act.